Schmitz 1985 gives “Winton, Edwin [i.e. The Bishop of Winchester]” – no doubt this is a mistake of some sort: the wins of Winton and Winchester make it easy to turn Edward into Edwin. Petrilli 2009 copies the mistake, omitting the Bishop (and errs in the number of the weekly).

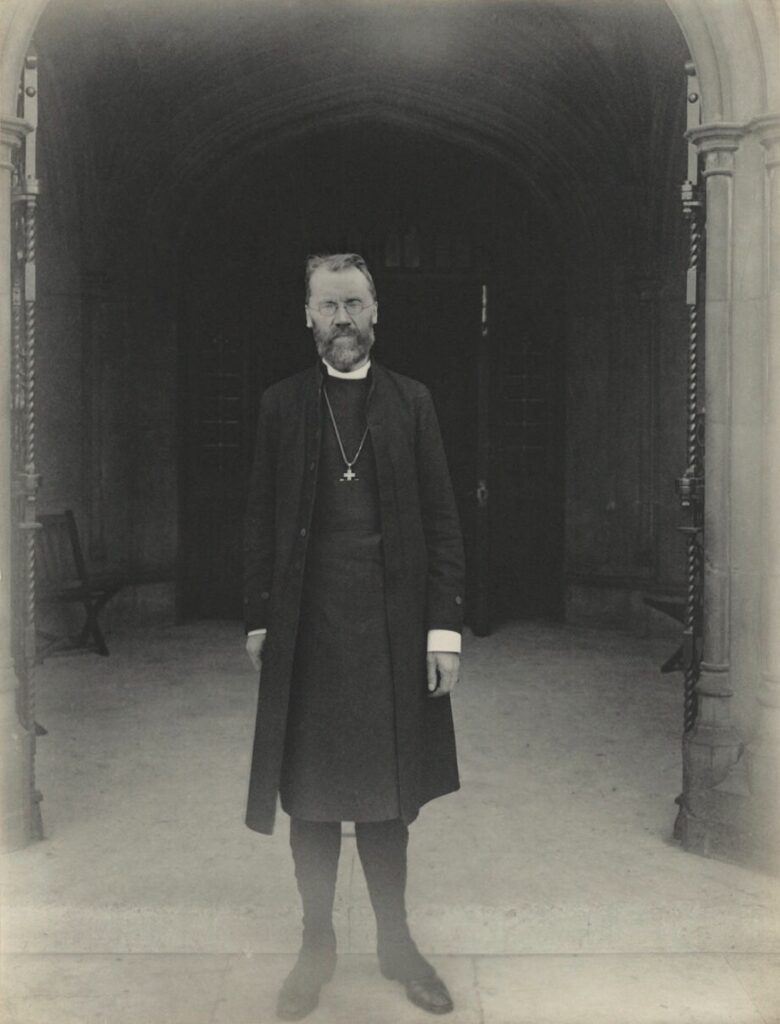

Edw. Winton, ‘The Late Victoria, Lady Welby. (To the Editor of the “Spectator.”)’, The Spectator, No. 4,371] for the week ending Saturday, April 6, 1912, pp. 543[11]–544[12].

Winton, short for Wintoniensis (of Winchester), is the signature name for the bishops of Winchester. Edw. Winton was Edward Stuart Talbot (1844-1934), Bishop of Winchester 1911-1923. Welby’s father, Charles Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie (1802–1844), was a brother of Talbot’s mother, Caroline Jane Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie (1809–12 June 1876), so Talbot was Welby’s cousin.

THE LATE VICTORIA, LADY WELBY.

[To the Editor of the “Spectator.”]

Sir,—In Victoria, Lady Welby, one of the most remarkable women of the Victorian time has passed away. What she would have been if she had been trained early in the things in which her mind found its congenial sphere it is idle to ask. As it was, she was left to find herself. Brought up by a very unconventional mother, left a solitary orphan at Beyrout in her eighteenth year, she came home to live the life of a young lady in society, to become maid of honour to Queen Victoria, to make a deeply happy marriage with a respected and practical-minded squire and M.P. She had obvious graces and gifts of mind and person, but there was, so far, no sign of any dominating mental influence over her life and no compelling purpose or vocation.

In her connexion with the foundation of the Royal School of Art Needlework she showed the vigour of her initiative and some real æsthetic distinction. These things appeared again when, as a country gentleman’s wife, she helped and guided him in the transformation of house and garden. But by this time other interests were growing to absorb her more and more. She disclosed very rare powers of intellectual questioning, insight, and suggestion. She made acquaintance by degrees with man after man distinguished in things philosophical, theological, scientific, and social, and her Lincolnshire home became a place of meeting for many men of high representative value. She read with omnivorous but concentrated interest the most exacting kinds of reading. Through it all she formed and revealed a mental temperament and ability which were, perhaps, in their way unique. People often went away puzzled, and often thought her disconnected and unsatisfying, but they seldom, if ever, failed to feel her power and to find that she had communicated to them abiding impulses or germs of serious thought.

Thinkers of the most various kind never hesitated to acknowledge that she could give and take with them, and had a quite extraordinary capacity in handling matters which are generally left to experts alone. Sometimes she would interpret, one to the other, men of different departments and widely separated lines of thought. It seemed to her that she saw through and beyond to things deeper than the antitheses of philosophical or other controversy and the limitation of special researches and speculations. The title of her first and perhaps best book, “Links and Clues,” was significant in more ways than one of the incompleteness and venturesomeness of her thought and of her keen interest in the unities of life and knowledge. Acutely and restlessly critical, her mental and moral interest was all for construction. She would give eager hearing to the most disintegrating speculations, and yet face the future with absolute confidence in the continuing and expanding revelation of the truth. It was in this vein of thinking that she came to what was the most absorbing interest of her later life, and the matter by which her name may perhaps find an abiding place in the roll of thinkers, viz., the relation of language to thought. She believed that many “insoluble” difficulties could and would be disentangled if we would be at pains to revise and control our use of words, helping ourselves by the best scientific analysis and, as she loved to insist, by the fresh instincts and intuitions of childhood. How far she was right time only can show. But she secured a place for “Significs” (such was the title) on scientific shelves and in learned debates. Few could distinctly grasp what she meant, but fewer still heard her speak or read her writing about the matter without feeling that she was in travail with things which she could not, for all her skill of imagination and dialectic, adequately express. She herself always believed that she was working for the future, and always looked modestly for some one who, with better equipment, would give more effective expression to her thoughts in time to come. She believed in glorious futures for thought and life. She thought she saw by glimpses how the great words of Spiritual Faith, God, Truth, Light, and Love would mean infinitely more and not less to those that come after. She was liberal, and no one would have called her orthodox. But through all her thought, however far it ranged through scientific, mathematical, and technical subjects, the central compelling force was religious. The profound moral instincts which had come pure and strong out of her early unsheltered life and the unity of God and the human spirit centred in Jesus Christ were to her illuminants and not restraints or limitations. Perhaps few will have left impulses of thought and influences of personal sympathy vibrating in so many people of such various kinds.—I am, Sir, &c., Edw: Winton.

Farnham Castle, Surrey.

[All who knew the late Lady Welby will be grateful to the Bishop of Winchester for his illuminating study of an intellect so attractive, and we had almost added so pathetic, in its passionate earnestness to seize the very heart and core of truth. She wrestled with words in order to obtain a mastery over the spirit behind them—the spirit which controls their true meaning, as the hero in some fairy legend wrestles with a magician who, if only he can be thrown, will turn beneficent and show the true path or divulge the great secret. Perhaps she was striving for the impossible, and yet one instinctively felt that she was knocking at the right door, even though it was barred so closely. Every one who has ever striven to think out thoughts to the end must have sometimes felt, if only for a moment, that there is a mystery in words which words cannot wholly express.—Ed. Spectator.]